|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, in a congressional hearing in May of 2022...

Cost plus has certainly been problematic in Artemis, but are fixed price contracts the answer?

Listening to the current messages coming out of NASA, one would think so, but the reality is considerably more complex and that's what we're going to explore.

We'll start by talking about the plague that is cost plus...

Cost plus is simple.

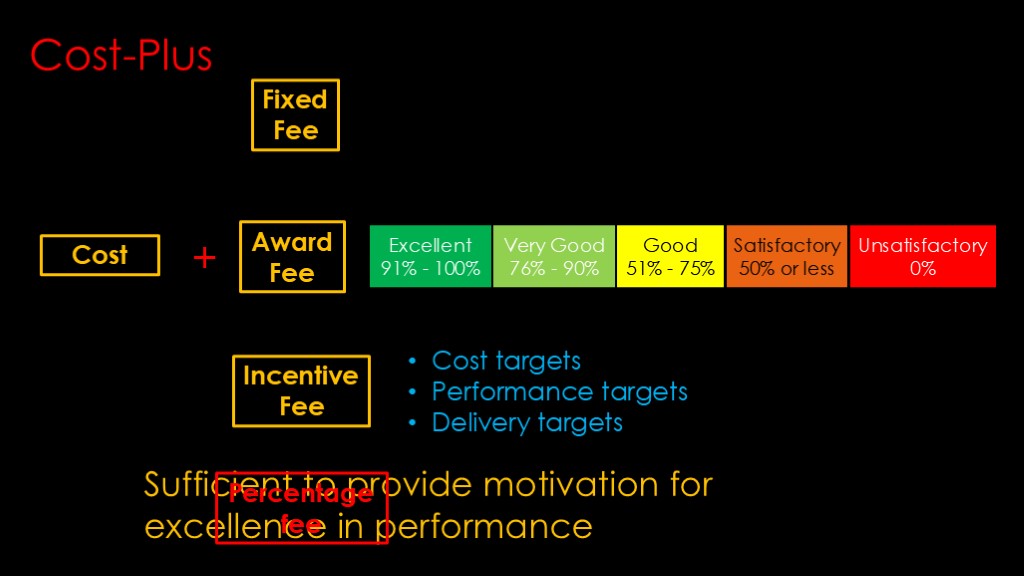

The contractor tracks their cost, and the government pays the contractor that amount of money.

The contractor gets their profit from one of three sources.

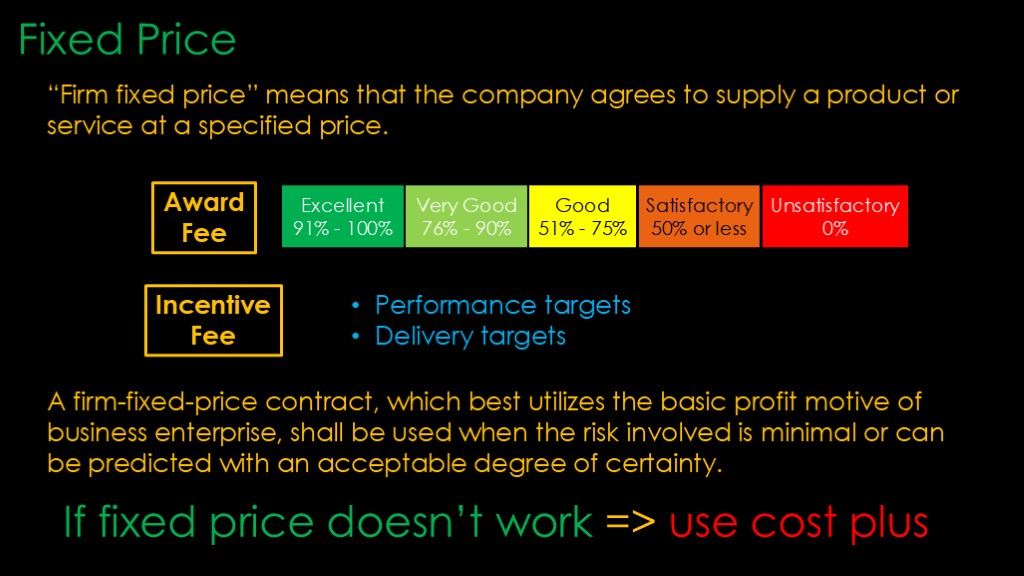

A fixed fee awarded at the completion of a project, an award fee awarded periodically as work is done based on the contractor's performance, or an incentive fee based on cost, performance, or delivery date targets. These fees can be mixed together if desired.

They do not get their profit as a percentage of how much they spend - that is known as "cost plus a percentage ", and it has been illegal in government contracts for decades. There is some benefit to contractors in higher costs, but it does not result in increased fee payments.

The government guide on cost plus says that these fee structures should be used in a way that is "sufficient to provide motivation for excellence in performance".

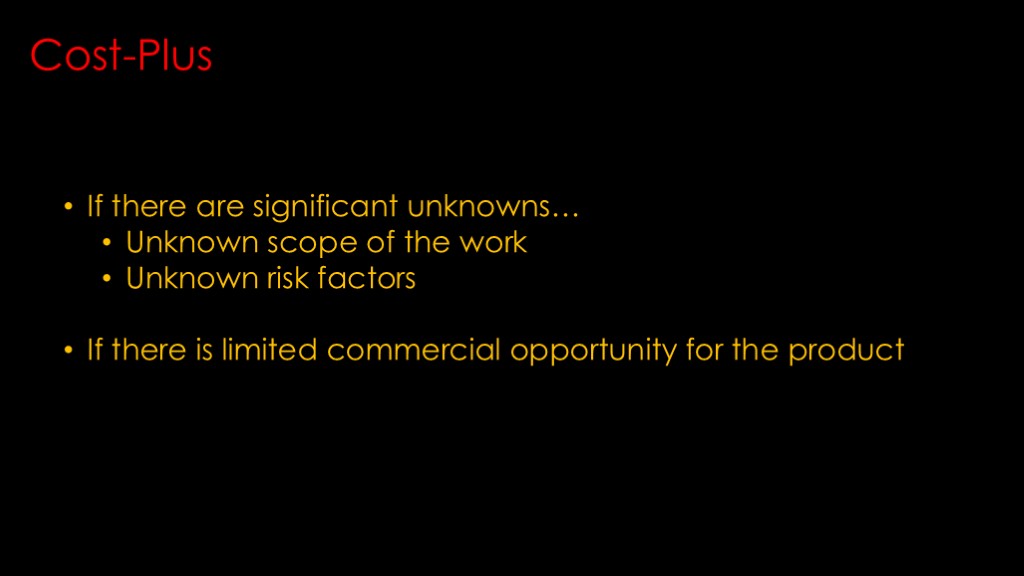

Cost plus does have overhead, so why would we want to use it?

If there are significant unknowns in the project - if the scope or risk factors are unknown, it's generally not feasible to figure out how much a contract will cost and therefore come up with a fair fixed price. And that risk means that there is a higher chance of failure with fixed price.

Also, if there's little commercial opportunity for the product or technology, there's less incentive for a business to take on the risk of a fixed price contract.

The main cost plus program in NASA in the last decade or so was - and still is - the SLS Rocket and Orion Capsule.

I am not going to delve into the details of how cost plus relates to SLS and Orion in this video, but I do have a few comments...

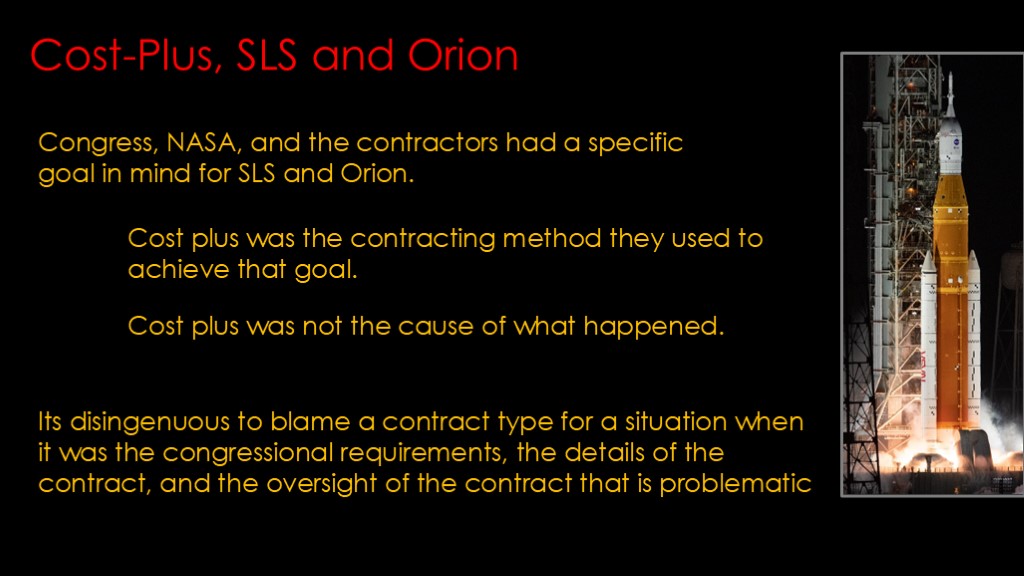

Congress, NASA, and the contractors had a specific goal in mind for SLS and Orion.

Cost plus was the contracting method they used to achieve their goal.

Cost plus was not the cause of what happened.

It is disingenuous to blame a contract type for a situation when it was the congressional requirements, the detail of the contracts, and the oversight of them that was problematic.

If you look at Bill Nelson's history, you will find that he was one of the main drivers behind SLS and Orion.

I'm feeling a rant coming on, so it's time to move on to our real topic.

Which is fixed price contracting...

Firm fixed price simply means the company agrees to supply a product or service at a specified price. The most obvious use of fixed price is when a product is on the market.

It's possible to add incentives to fixed price contracts if you care about something other than price.

The government gives the following advice on the use of fixed price:

(read)

If fixed price doesn't work, then it's appropriate to use cost plus. That's why cost plus contracting exists.

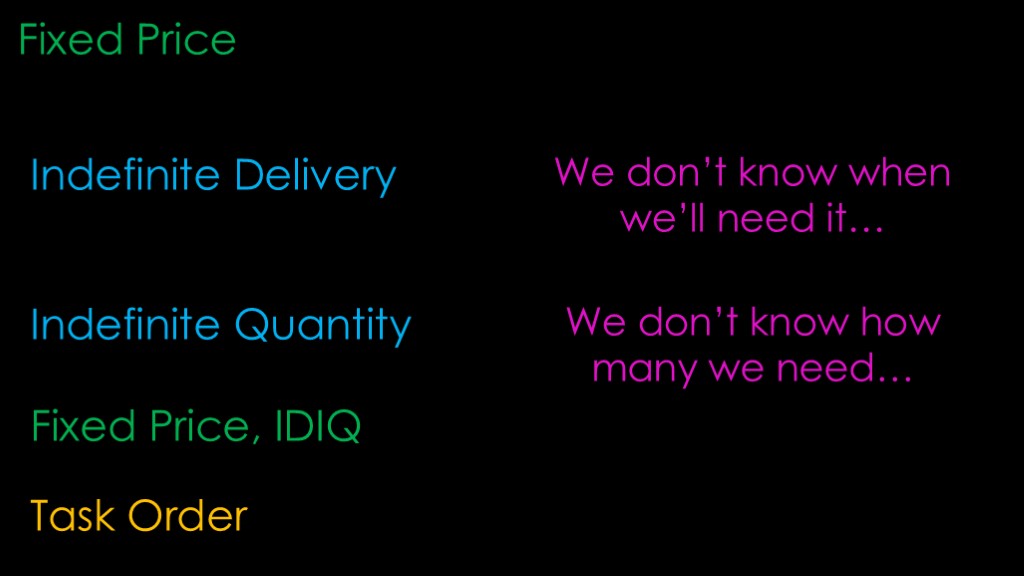

There are two very common variants of fixed price contracts.

The first is indefinite delivery, or "we don't know when we'll need it". NASA's contract with SpaceX for crew flights to ISS is indefinite delivery because NASA doesn't know at the time of the contract exactly when they will need them.

The second is indefinite quantity, or "we don't know how many we need". There is generally a base quantity in the contract with options for up to a maximum quantity at specified prices. If you see contracts that say "up to $3.2 billion" that number is for the maximum quantity.

These contracts specify enough units so that the contractor can provide a good price but do not constrain the buyer to a specific schedule.

Contracts that have both of these will say "Fixed price, IDIQ".

To order and schedule delivery, the government will send the contractor a task order.

Now that we've covered the basics, let's look at fixed price at NASA.

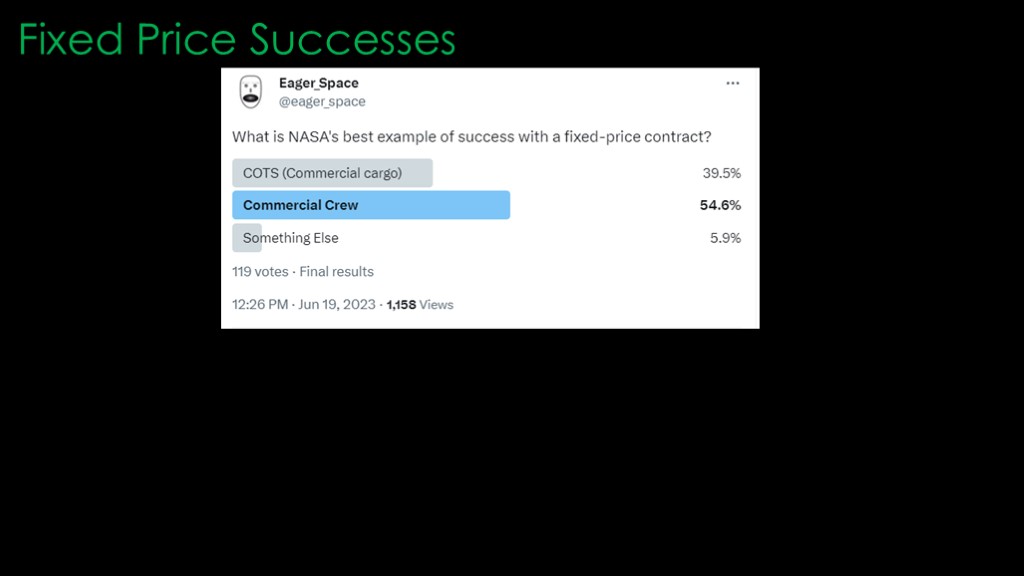

We should start by looking at the success of previous fixed price contracts.

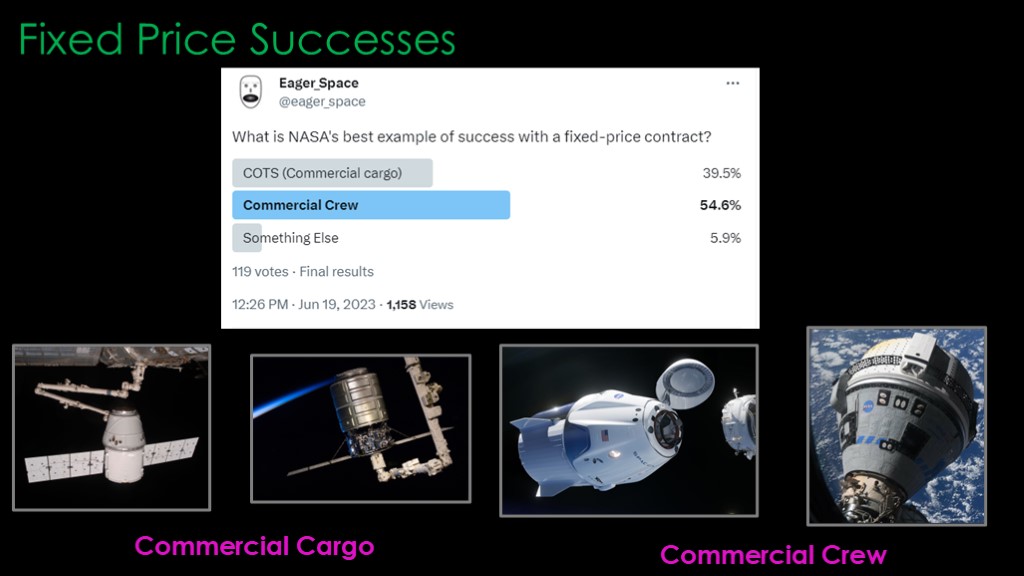

I asked my twitter followers what is NASA's best example of success with fixed price contracts. I got a great reply that is clearly the right answer but isn't one of my choices...

The correct answer is NASA's launch services program, which is how NASA's science payloads find a ride into wherever they are going.

It meets the "risk can be predicted with a high degree of certainty" requirement very well, and as a program, it just does what it is supposed to do. Nobody talks about it because the program is such an obvious use of fixed price contracting and competition.

I instead want to talk about the flashy programs.

My followers thought that commercial crew was the best fixed price contract, with commercial cargo coming in second.

As is often the case with my polls, it was a trick question, because neither commercial cargo nor commercial crew were fixed-price contracts, at least not in the development phase. Neither were they cost plus contracts.

Which doesn't make sense, as those are the only two contract types permitted under government regulations.

The explanation requires a journey back into history.

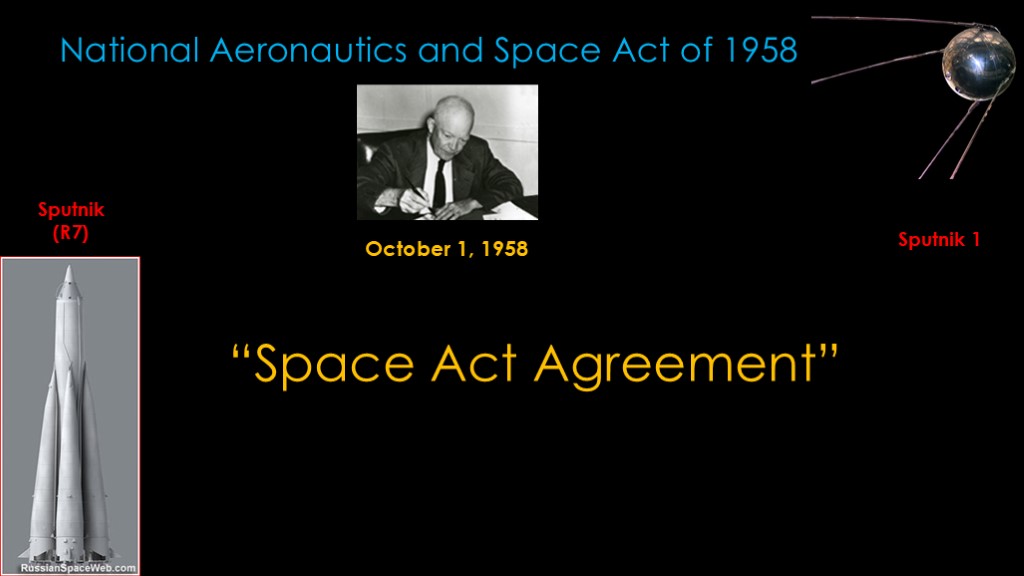

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik 1 satellite on top of their Sputnik rocket, derived from their R7 missile. This led to a lot of concern in the US, known as the sputnik crisis.

Congress wanted to do something to help the US catch up, and they passed the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, which was signed by president Eisenhower on October first.

Congress wanted the US to move fast and was worried that following the usual budget rules would slow NASA down, and they therefore granted NASA a sort of budgetary superpower to bypass those rules and come up with their own rules.. You can think it as a "what if we just threw money at the problem?" option.

That power was defined in the space act, and using it is therefore called a "space act agreement"

If NASA comes across a situation where they believe that Fixed Price or Cost Plus contracts will not be effective, they can choose to use a space act agreement instead and create their own contract terms.

Like all superpowers, it requires great responsibility on NASA's part and therefore there's a defined process to use it, but it is a very useful tool when deployed effectively.

Since commercial cargo was first, we'll start there...

In the early 2000s, NASA had a problem - the shuttle was retiring in the early 2010s, and there was no US replacement to take cargo or crew to the space station that NASA had spent so many billions of dollars building. If NASA didn't come up with a solution, they would be paying for the Russian progress and Soyuz vehicles to fly both astronauts and cargo.

NASA was hoping that the constellation program would be that solution, but it wasn't clear when it would show up...

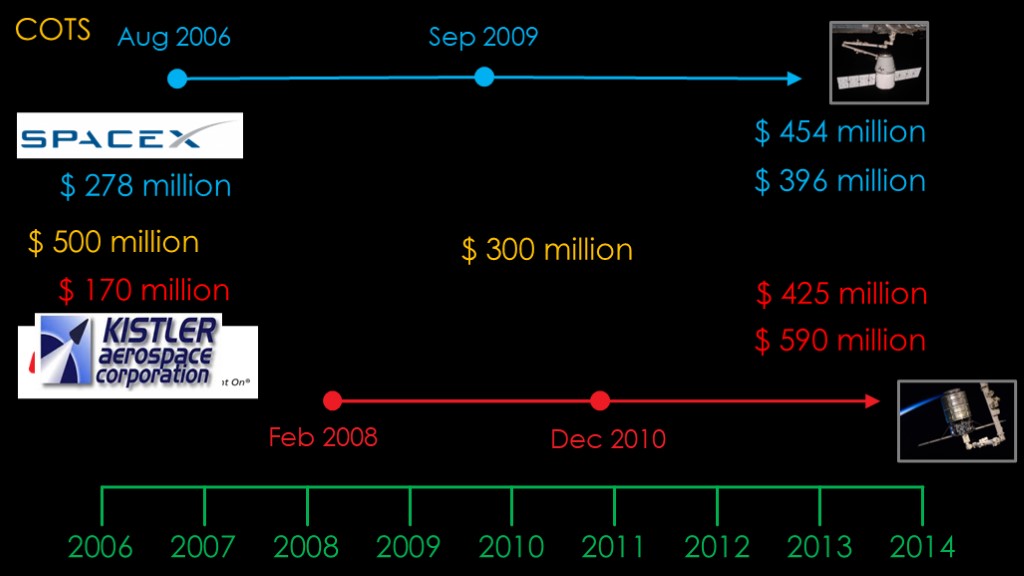

... and in line with Congress' mandate for NASA to use commercial solutions, NASA spun up a program known as the commercial orbital transportation system, or COTS. Congress kicked in $500 million to fund it.

NASA initially selected SpaceX and rocketplane Kistler as the two participants, introducing the now-familiar concept of "two provider redundancy". Kistler was unable to meet the private financing goals in the first year, and they were replaced with Orbital Sciences.

Of the $500 million allocated, $278 million was budgeted to SpaceX for Falcon 9 and Dragon, and $170 million to Orbital for their Antares rocket and Cygnus resupply module.

The contracts were structured with a series of milestones and a payout associated with each milestone. If that sounds like a firm-fixed price contract, you're on the right track, but NASA knew at the outset that this was a hard problem, and they chose to do these contracts as space act agreements.

SpaceX had a goal date of September 2009, and Orbital aimed for late 2010 because of their later start.

By late 2009, it became clear that neither of the companies were going to make their target dates, and - more importantly - they wouldn't be able to do it for the agreed-upon amounts. SpaceX simply did not have the money, and the $170 million orbital would get simply wasn't worth the effort.

Luckily, NASA, the advisory commissions, and congress all agreed, and a further $300 million showed up in 2010 - in the same legislation that created SLS - and the program could continue, with both contractors achieving success by 2014.

The program ended up a huge bargain for NASA, with their total investment at $821 million, less than the shuttle yearly budget for upgrades, and the per-kilogram costs for cargo to ISS were quite a bit cheaper than shuttle...

They were less successful for the two contractors, as they ended up putting a lot of their own money into the program, with SpaceX investing $454 million and Orbital investing $590 million. Orbital was an established company and they would happily earn their investment back in flying cargo to ISS, but SpaceX did not have significant cash reserves, and it was only a combination of Musk's Silicon Valley contacts, the launch backlog that existed at the time, and the constant work of Gwynne Shotwell that kept them afloat. It was a close thing.

NASA talks a lot about private/public partnership and I think that it's generally a good thing, but I think there needs to be an equitable balance. Both SpaceX and Orbital invested a lot of money to develop capsules that are only used for ISS resupply because a commercial market does not exist.

SpaceX did get Falcon 9 out of it and that has been a huge benefit to both SpaceX and NASA, but Antares only flies ISS resupply missions.

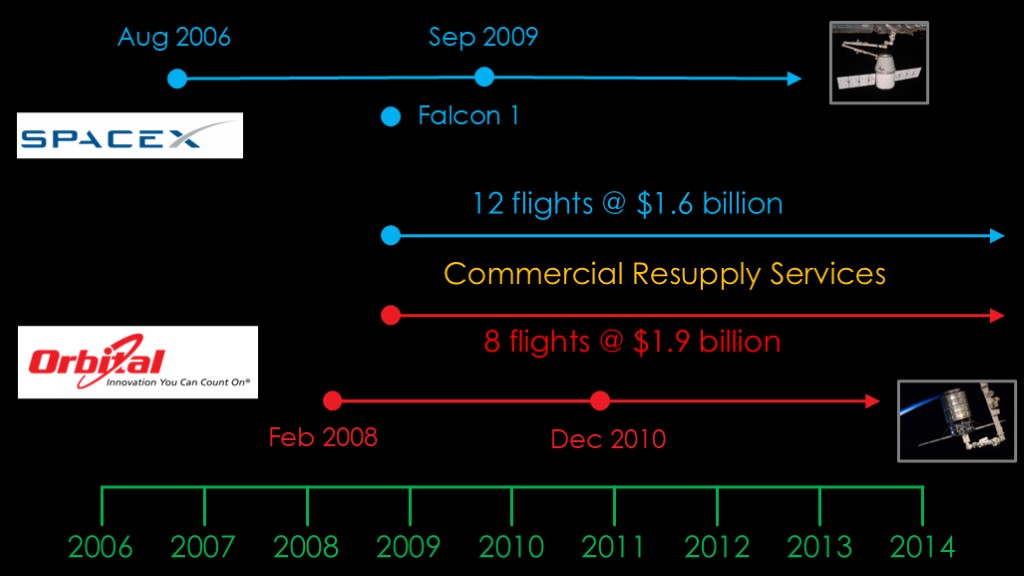

There was, of course, a fixed price program known as commercial resupply services for the actual resupply flights, and that seems like a appropriate place to use fixed-price.

The problem was that NASA really wanted to start supply flights early to avoid relying on the Russians, and that meant those contracts were awarded in 2008, and that meant SpaceX and Orbital needed to put in bids for flights of vehicles where they could not adequately determine their costs. Orbital had been working on the program less than a year, and SpaceX had yet to successfully reach orbit with Falcon 1

In that environment, fixed price was not appropriate, but that's what NASA decided to do. Orbital bid a price that would let them earn back their investment, and SpaceX significantly underbid because they really really needed the contract.

SpaceX would later get dinged for raising their prices significantly for the second set of CRS contracts, but they were actually just adjusting their prices based on their actual costs.

My overall evaluation of COTS is that it was NASA's flexibility to go beyond firm fixed price that made it possible, and they got lucky that SpaceX showed up.

Commercial crew also used space act agreements.

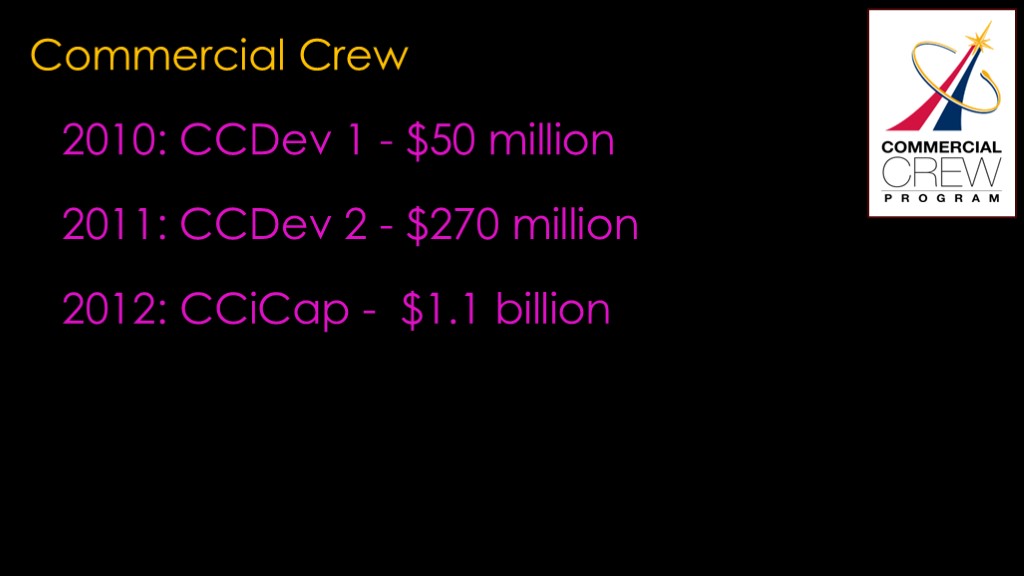

In 2010, CCDev 1 gave out a total of $50 million to 5 companies to work on things related to commercial crew.

In 2011, CCDev 2 expanded this considerably, with $270 million to 4 companies.

In 2012, the CCiCap program gave out $1.1 billion for 3 companies to create a fully-thought-out plan for how they would do commercial crew. This was a *lot* of money - the $440 million that SpaceX received was more than they received during COTS for developing both Falcon 9 and cargo dragon.

NASA's choices were in line with NASA's traditional development approach - do a *lot* of planning up front before you start so that your execution will be fast and clean.

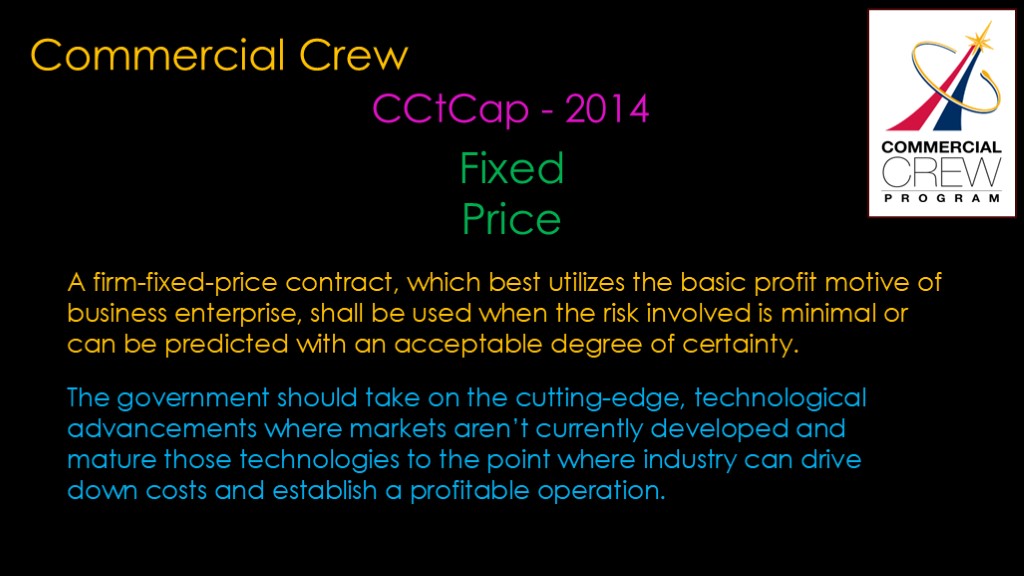

For the development program - known as CCtCap - NASA decided to go with a full fixed price approach.

Let me bring up the acquisition guidance again...

Was the risk minimal or easily predicted? The US hadn't developed a crewed vehicle since shuttle in the 1970s, so nobody in the industry had recent experience.

NASA did a study after COTs, and this is one of their lessons learned (read)

Was commercial crew a cutting edge area where markets aren't currently developed?

I would say yes, and even a number of years later, there is only a tiny market for commercial crew transportation.

Which means that fixed price isn't really the appropriate choice.

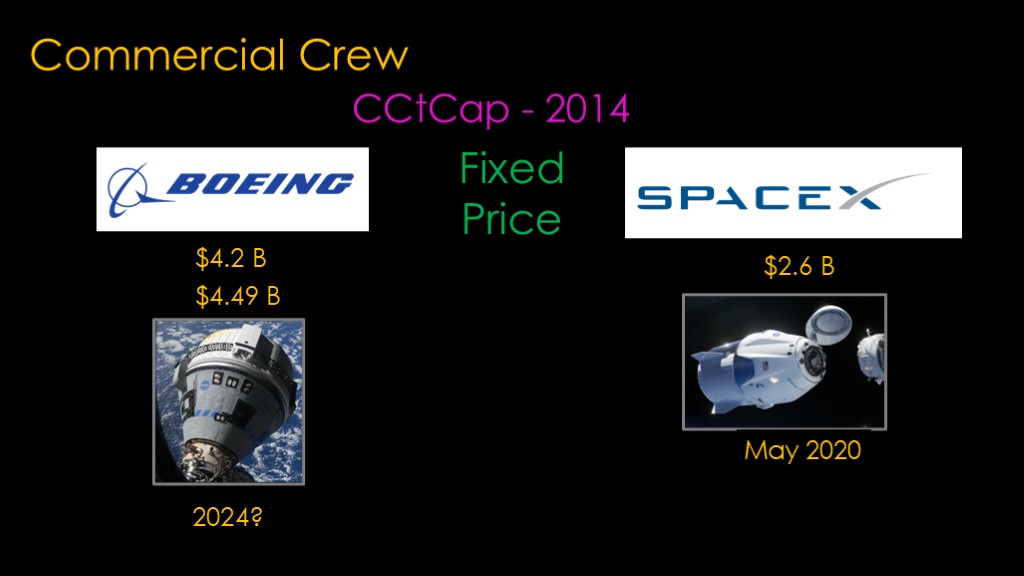

The contracts went to Boeing for $4.2 billion for their Starliner capsule, though they convinced NASA to cough up another $287 million along the way. SpaceX got $2.6B for Crew Dragon.

SpaceX finished their test flights in May of 2020. This was later than NASA hoped, but it's important to remember that congress underfunded commercial crew significantly in the first few years, and the NASA "Crew Rating" process that both contractors needed to follow didn't even exist at the start of the program.

In the summer of 2023, Starliner has yet to fly crew, and 2024 seems to be the earliest opportunity.

In retrospect, I think this result should have been easy to predict. SpaceX had the relevant experience from cargo dragon and they understood how to work under fixed price contracts.

Boeing didn't have recent capsule experience nor were they used to working under fixed price approaches.

From the perspective of what NASA hoped to accomplish, they got one real success and one incomplete. People like to make fun of Starliner and Boeing certainly bears most of the blame, but this project has turned into a significant problem for them and they have already spent $900 million more than they planned. Fixed price limited the cost from the NASA perspective, but NASA still has spent a lot of time and money on Starliner without any return.

Time for the big boys, the Artemis lunar landers.

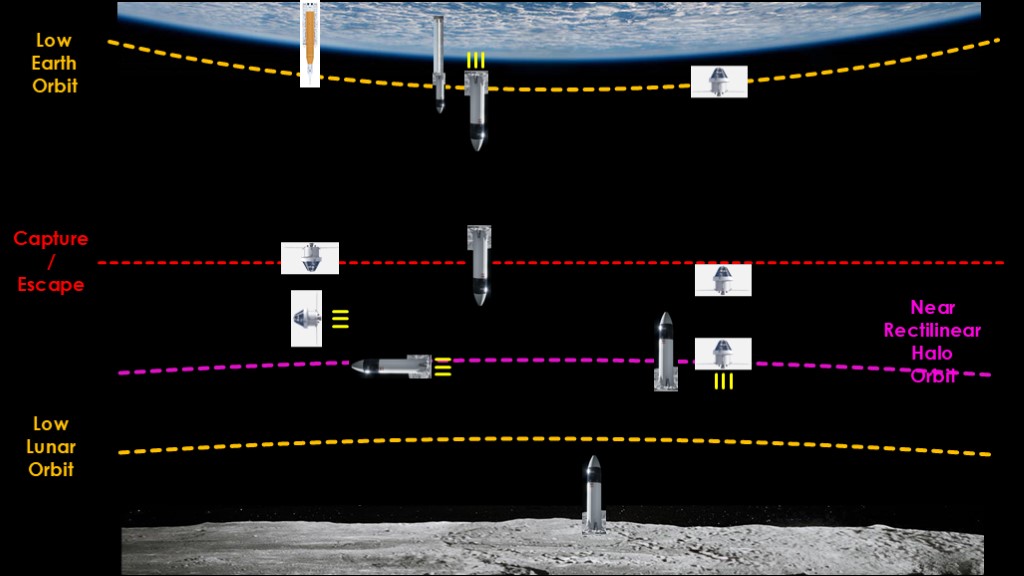

Here's how the architecture works.

SLS tosses the Orion capsule on the way to the moon, and then the Orion brakes itself into near rectilinear halo orbit around the moon.

The lander gets into orbit, does whatever it needs to get fueled for the trip, and is sent on the same trip as Orion, getting into orbit along with Orion.

The astronauts transfer to the lander, land on the moon, stay for at least 6 days, then they return to orbit, the astronauts get back in orion and head for home.

What the lander has to do is by far the hardest thing that has ever been done in crewed spaceflight, quite a bit harder than what was done with Apollo.

Based on what happened in commercial cargo and crew, how would you structure the contracts?

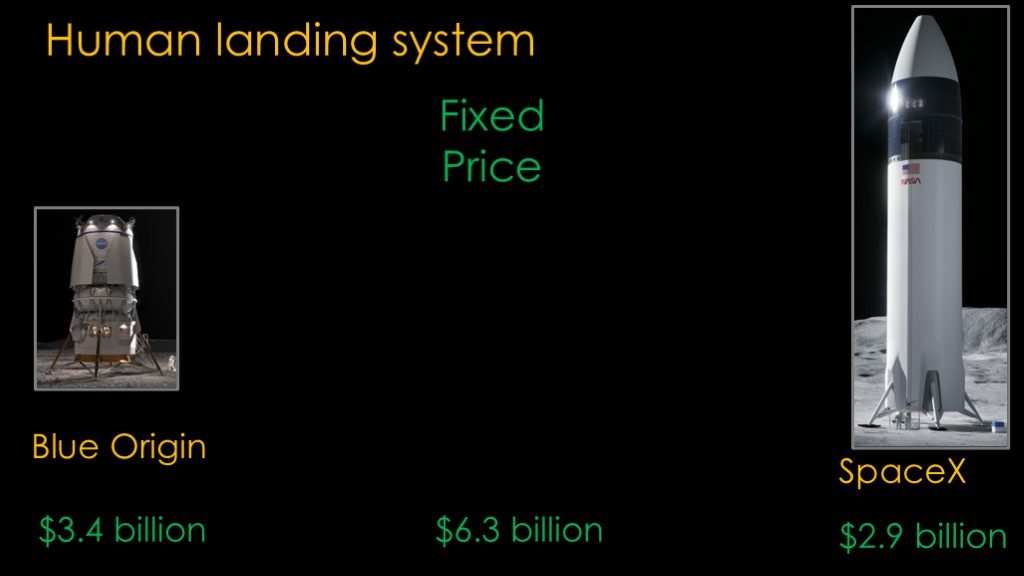

NASA decided that the appropriate contract structure is... Fixed price, with SpaceX getting $2.9 billion and Blue origin getting $3.4 billion in a later contract.

NASA is in a budgetary crunch. Wayyy back in 2010 when SLS and Orion were designed to fill in the shuttle-sized hole in the budget, Artemis didn't exist and therefore it was fine to spend the majority of the budget on those two programs.

But now, NASA has actually said they are going back to the moon, and they just *do not* have the money to do it right. They plan to spend $6.3 billion on these two landers, pretty much the same they spent on two capsules to take astronauts to the ISS.

So they are depending on the fact that there are two billionaires who are interested enough in the moon to put in governmental amounts of their own money.

Because of the way the economics work out, instead of NASA being the driver of this program, they are now beholden to two companies that will do whatever they want to do. There's no schedule that NASA can hold them to, and it's possible that either SpaceX or Blue Origin will get tired of the project and just stop working with NASA.

And that's assuming current NASA budgets, and there's a possibility that NASA will see deep cuts in the next budget deal.

NASA had been working on a new lunar spacesuit known as the xEMU for years, but after $420 million spent over a decade, they decided to go commercial.

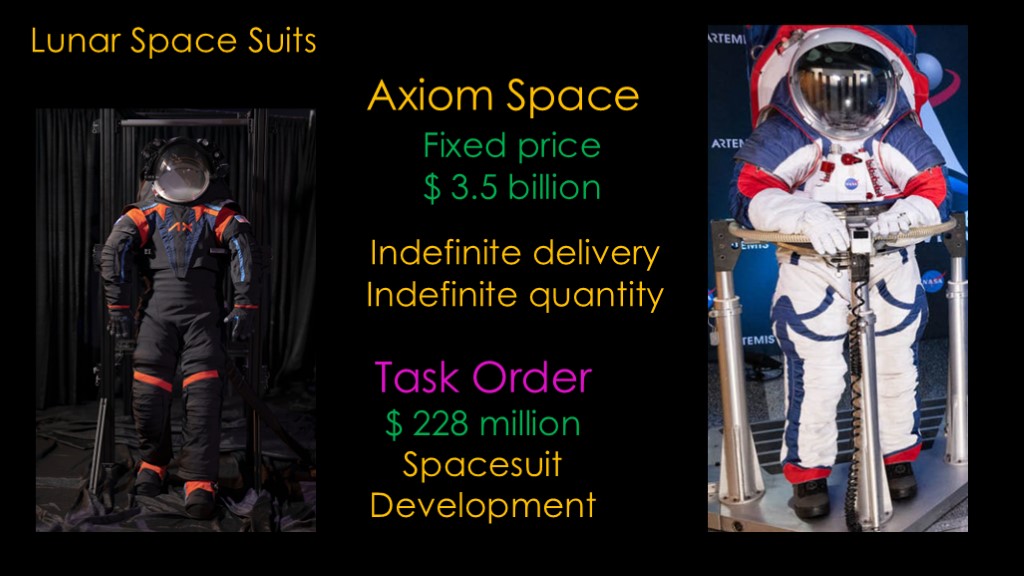

The contract for the lunar space suit went to Axiom Space, a company with no previous experience in space suits, but one of two companies that expressed interest. The other company is Collins aerospace, and they got the contract to develop a new orbital space suit.

This contract has unknown risk in an area with unknown commercial potential, and therefore the contract that they chose was "fixed price" for $3.5 billion.

It's at this point that I realized something. This is a perfect situation for either a cost plus or space act agreement to both share the uncertainty and risk with NASA and because it's hard to imagine when a commercial market for lunar suits might show up, but "cost plus" is a bad word at NASA and for some reason space act agreements aren't allowed either.

I have no idea where the $3.5 billion number came from - it's clearly a case of "let's throw some money at it".

The contract is an indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract, which also makes no sense. That what you would use to buy resupply flights, not to do research and development.

NASA has recently sent Axiom the first task order. It's not to actually buy a spacesuit, it's $228 million to spend on developing a spacesuit. It looks exactly like a space act agreement, but it's hiding inside a fixed price contract. I'm really surprised that the NASA inspector general and the General Accounting Office aren't all over these contracts, as it looks like a very obvious attempt to circumvent the fixed price regulations and invent a new kind of contract, one that NASA can already do with space act agreements. The obvious reason to do this is that space act agreements require high-level review, and fixed price contracts do not. And everybody knows that fixed price is better.

It's clear that neither NASA nor Axiom have any idea what the suits will actually cost. That's not a dig at Axiom - nobody has designed lunar suits since the mid 1960s, and I don't expect them to be able to cost things up front.

It is a dig at NASA, who should really know better.

Which brings us to the NASA commercial lunar payload services program, or clips.

The idea of CLPS is pretty simple - NASA needs to do exploration and science on the lunar surface before the Artemis landings, and rather than create a lander and probe themselves, they will farm it out to commercial companies that will provide the lander and perhaps a rover for the NASA science instruments.

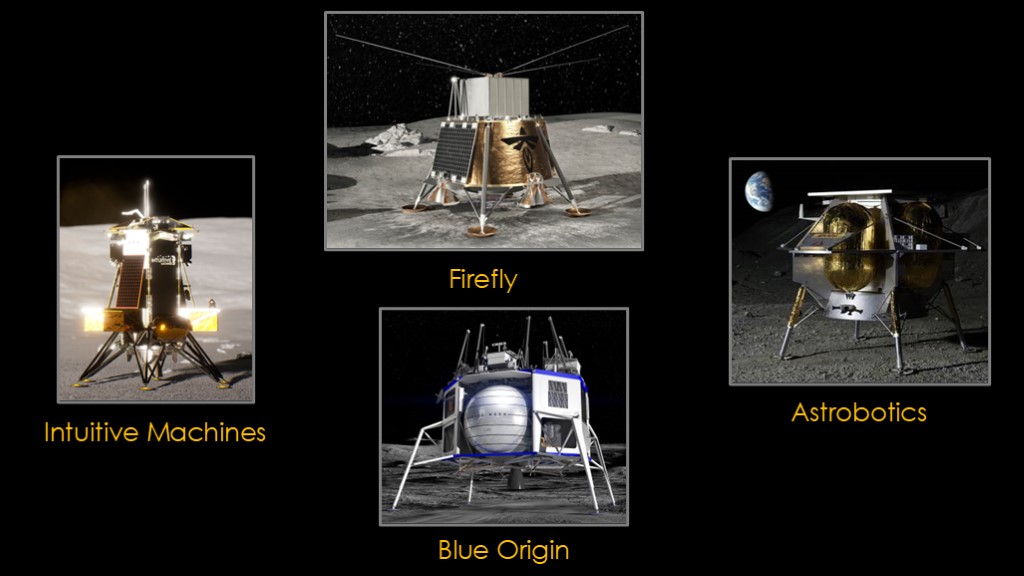

There many companies involved in this program - intuitive machines, firefly, astrobotics, blue origin, and a bunch of others.

The program sounds great, conceptually. But there are a few issues.

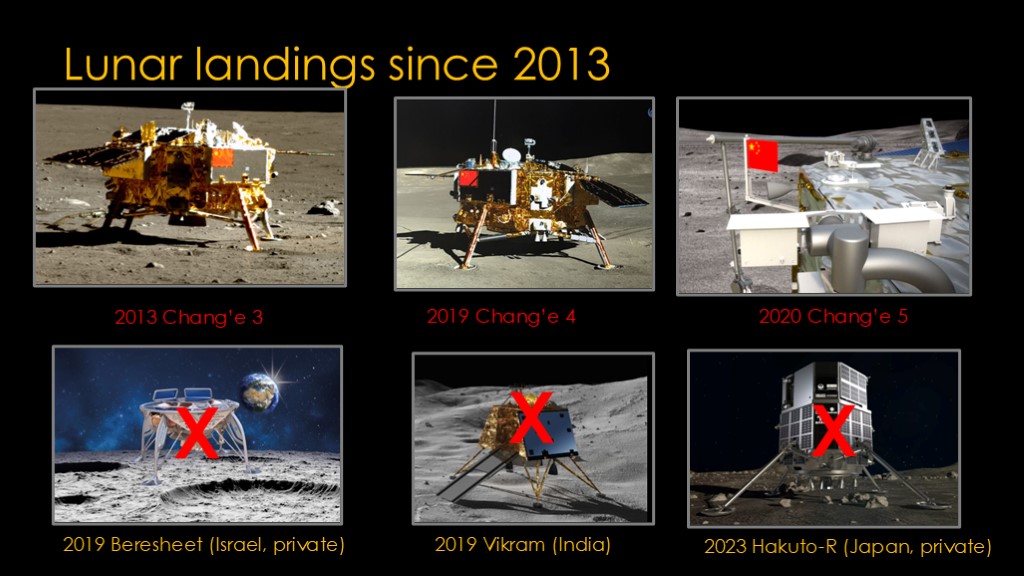

China has been knocking it out of the park, with three successful lunar landings in the last decade.

In 2019, the Beresheet lander by a private Israeli company attempted to land. It crashed.

Later that year, the Vikram lander from India attempted to land. It crashed.

In 2023, the private Kakuto-R lander from Japan attempted to land. Are you surprised to find out that it crashed?

The reality is that navigating to the moon and successfully landing is a really hard thing to do, and failures are not surprising.

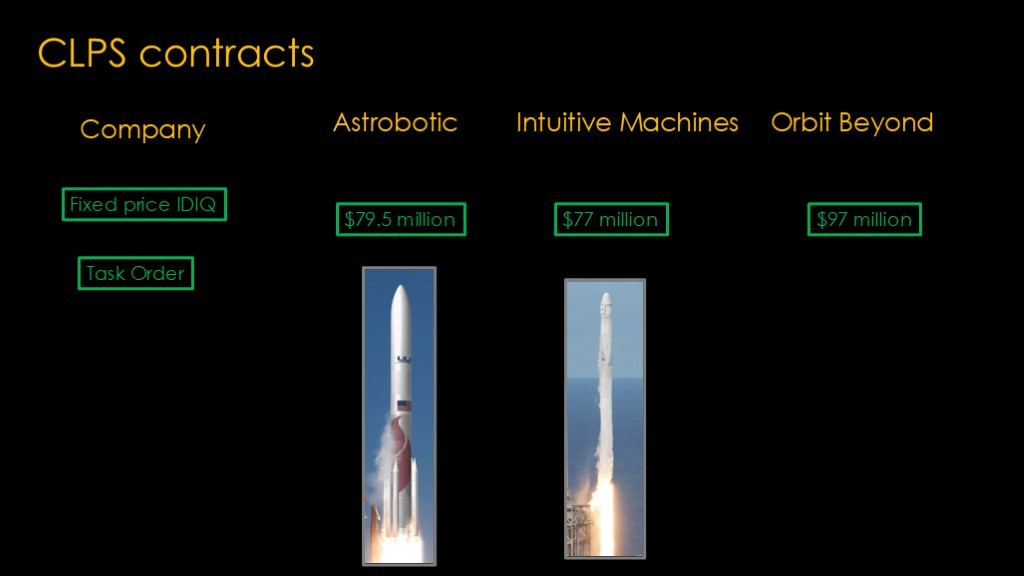

The contracting approach of the CLPS program is like the Spacesuit contract.

Each company has a fixed price indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract, but they are truly indefinite - there is no defined amount of money or delivery. They are just containers for task orders that the company might win.

In May of 2019, NASA gave out the first three task orders, all for landings on the moon, to astrobotics, intuitive machines, and orbit beyond. Orbit beyond dropped out 2 months later, not an especially auspicious beginning to the program. Astrobotics got $79.5 million for their first mission, and Intuitive machines got $77 million.

Those prices are the end-to-end prices; the provider is responsible for developing and building the lander and obtaining launch services to get their lander to the moon. The idea is that the contractor can find other commercial payloads to fly and help defray the costs.

Astrobotic's first lander will fly on the first flight of Vulcan, which presumably gets them a discount on launch costs for their first flight. Intuitive machines will fly on Falcon 9.

I see no way that the economics can work out for these companies. Subtract the cost of the Falcon 9 for the intuitive machines, and they have something like $20 million left. That has to be enough to develop their lander, do all their testing, build the lander and operate it on the journey and while on the moon. If they can sell payloads, they'll get a little more money, but it won't be a ton. It's not clear to me what happens when - not if - but when these companies run out of money. Is there a "here's a little more money task order"?

NASA is putting high-value science experiments on these vehicles to guide their Artemis planning, but given the demonstrated difficulty of landing on the moon, this will not end well.

NASA has had great success with programs where they pick the two best companies out of all that are interested, throw them some development money to get up and running, and then go from there.

I'm utterly at a loss to explain why they have chosen this approach for clips.

To return to the original question - whether fixed price contracts are the answer - apparently the answer from NASA is "yes, because you can play tricks to make them look like cost plus contracts or space act agreements".

There is a role for all the contract types in NASA contracting, depending on the type of project they are doing.

If you enjoyed this video, (read)